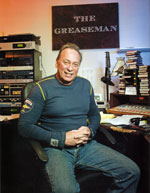

"I'm Almost A Trained Schizo"

Even Doug Tracht, his alter ego, seems to realize that sometimes the Greaseman cometh on too strong

By Gary Smith

Photographs by Tom Wolff

November 29, 1987

The Washington Post Magazine

AT 3 A.M. IN A CONDOMINIUM IN NORTHWEST WASHINGTON, AN ALARM CLOCK rings and Doug Tracht fills with dread. Soon, like millions of other people, he must walk into an office and become someone else.

He punches off the alarm on the closest clock, then on a second, a third, a fourth and a fifth. What would become of him if he slept past the time when he was supposed to become his other?

He lies on the bed beneath the figure of the Virgin Mary clutching the baby Jesus that his bride picked out for the wall, lies there and tries not to think. From beneath the sheet he feels his wife's fingers. Blank he keeps his mind as they dig into his shoulders, then his back, then his hips, kneading him from head to toe each morning as if pressing something from him.

He steps under the shower, sings hymns he learned as a choirboy in the Lutheran Church and lets water begin to wash Doug Tracht away. He is nearly ready now to give way to the other; but, no, he must not plan for it, that could only interfere.

He kisses his wife, one of the few people he permits inside his private world, takes the breakfast she has packed him and drives his High Sierra Ranger through the dark, empty streets. He must be in place, waiting, changed, when the rest begin to stir. At his desk he eats the carefully sectioned wedges of melon and the cereal with almond slices, and reads the note she has written to "My Sweet T-Bird" or sometimes to "My Little Boy," tucking it into a drawer with scores of others from her he cannot bring himself to throw away. Then he slips behind a consol jammed with buttons, cracks his knuckles, leans into a microphone and begins to speak.

"Good morning, every-BUDDYYY! This is the Greaseman on WWDC and today I feel bold, i feel bulky, I feel testosterone pumping through my veins!"

Soon he's into a story about a cop frustrated with his superior. "So you let fly with an unsavory spiraling wad of mu-COS-ah that slams into his blotter. He stares horrified at the GLOB-ules soiling his report, and this time you hock a NASTY mu-COS-ah-laden wad on the front of his shirt and he looks totally horrified at that probably DISEASE-laden, BACTERIA-infected boo-GERRRR that sits proudly on his uniform...Then you let him have one right between his eyes and as the mucous DRIPS down his face..."

The sun has barely risen, the morning still smoky with dawn, but the dread has gone, the exchange made; he, unlike the others heading to their jobs, is becoming borderless, fearless, free.

"...and as my honey dropped me off at the station this morning, i put a lip-lock on those full ripe lips, those bodacious TA-TAS crushing against my chest..."

It is all in code, of course. Ta-tass mean ---- and doodads are ---- and hydraulic s ---- and tookas is ----, and all across the city and its suburbs, bricklayers and carpenters sip coffee from styrofoam cups and snicker, and government clerks in neckties and traffic jams shake their heads in disbelief and laugh the Devil's laugh because someone, thank God, someone has the doodads to kick order in the tookas, send it somersaulting through the air and landing on its ----.

"I knew a girl drove a Lamborghini

Had a nice face but her boobs were teeny."

A genius, many call him, referring to the long stories he weaves projecting himself as a lawman blowing away criminals, Sergeant Fury blowing away Vietcong, a mob hit man blowing away double-dealers, using sound effects and accents and an unplanned, lightning-bolt talent with words to create theater of the mind; in truth, it is not fair to his humor to extract just a few lines from it, wring it of his voice inflections and hang it out to dry in print.

Repulsive, others call him, outraged by the ethnic and sexist jokes, by the three or four orgasms he simulates most mornings, the five or six theater-of-the-mind gobs of spit he launches and describes in mid-arc.

"Washington's Best Deejay," The Washingtonian has named him for five straight years, based on annual reader surveys. "The Voice Of The Devil," cried a minister in Florida. "Fry the Greaseball," urged signs toted by picketers in a 1986 protest outside the station's offices after he had slurred the memory of Martin Luther King Jr. For affecting people so, his station pays him about $400,000 a year, making him the city's best paid deejay.

And every place he works, when his shift ends and he feels himself go limp, the people in his office watch him walk out and shake their heads, discussing him as if he were two.

"Doug Tracht? A wonderful guy. The Greaseman? Sickening." This from a woman currently working at his station.

"The true Doug? A shy, quiet guy with strong values, a man who wouldn't hurt a flea." This from a former colleague and college roommate name Jim Stevenson.

"To tell you the truth, i always felt his real self is the Greaseman, and Doug Tracht is the phony." This from Pete Owen, a deejay at his previous station in Jacksonville.

"An introvert who could become what he really wanted to be on the air, because he didn't have to look at anybody." This from another deejay at Jacksonville.

The listeners who only hear his voice feel something different. "I'm up on my ladder painting every day, watching all these people walk by in their nice clothes," says a local fam named Eddie Scott. "They're perfect - but then they walk around the corner and pick their noses. The Greaseman, he's himself. The Greaseman, he's free."

EVERYTHING I SAY IS EVERYTHING YOU ever dreamed of or wanted. I'm raising your heart rate. I'm making your skin perspire. I'M affecting YOU.

"It's funny," says Doug Tracht. "I remember very little of my past. When an unpleasant thing happens, io resolve never to let it happen again, and then my mind shuts it out, as if it never happened. It's funny..."

Running. Vaguely, when his sister brings it up, he remembers running. Stretching his spindly legs and arms and running down the Grand Concourse in the South Bronx, dipping around a corner, eyes big, skinny torso heaving. They're coming, a whole pack of them, they're coming. Ducking inside a paint store, begging the old man who owned it to keep quiet, darting into a stockroom and waiting, heart pounding, shaking in the shadows. They're coming.

The hallways. Vaquely he remembers the hallways. Walking down the DeWitt Clinton hallways curled up inside himself like always, and all at once out of the gloom a random punch in the belly.

His bladder. A little sip of water for lunch, then holding tight his bladder, 1, 2, 2:15, hurry, clock, hurry; all those years without going to the school bathroom because they might be in there waiting.

Let me hold your lunchmoney. Vaguely, yes, now that a friend from school brings it up, he remembers the phrase, the outstretched hand, the glower. Giving them the lunch money, going hungry, so the gangs taking over the South Bronx in the '60's wouldn't beat him. The 3 p.m. bell. The perspiration on his skin. The sprint, head swiveling, skinny torso heaving. They're coming, aren't they? They're coming.

"I'd forgotten all about that," he says. "It's strange..."

"It's 3 minutes after 7 o'clock as we face a new day, and i'm crackin' my knuckles in anticipation. I think i'm up for a little bit of brutality. What do you say? BRU-TAL-I-TYYY! Does that sound nice? Do you feel like hearing the sound of fists cracking against cartilage, do you want to hear the whoomph of air as it leaves somebody's lungs? ...Time to wonder what it must be like to strap on a gun, and pin on a badge...and become a LAW-MAAAAAAN!"

Hours he spent in his bedroom, blankets covering the windows to protect the glass, pillows arranged carefully inside a crate to keep the lightbulb shards from flying, squinting down the BB-gun barrel, squeezing the trigger and feeling the flush as the light bulbs shattered. He would be a skeet-shooter when he grew older, a member of the National Rifle Association, and he would don fatigues as an adult to take part in war games in Virginia.

Reading was his other passion. Holed up in his room, he read of brave men in wooded places, overpowering their enemies and forging frontiers far, far from that rotting hellhole of a city. He stayed one night in a friend's backyard tent and hated it. His frontier would be a different one.

Vomiting. Vaguely he remembers the blind date, the hot shame on his skin, the burning consciousness of his 6-2, 120-pound body, his acne, his think, straight hair, his Coke-bottle glasses with thick black frames. Getting away from her, shaking inside from nerves, vomiting. And never dating in high school again.

Then on to Ithaca College, vowing to make it change. Did it happen to Doug Tracht or was it something he dreamed? Distantly he remembers walking into a bar and watching for awhile, then walking up to a girl and risking "Can i buy you a beer?" He remembers her looking at him, her saying no, and then turning and leaving him with the thing a radio man dreads most; dead air.

"...and as we're studying in the library, she kind of reaches out with her foot and starts tickling the calf of my leg...She saw me SQUIRM and thought it was funny...Now she's getting me HOT and BOTHERED...She's starting to make my jeans fit tiiight...She leaned forward showing her MASSIVE Eldridge Cleavage. I saw those ta-tas and I just had to LICK...the back of her neck. People were starting to look at us. I said, 'Estelle, let's get behind this bookcase...'"

Aboriginal sounds. Vaguely, when the anecdote is relayed from his junior high buddy Ernie Wilkins, DOug Tracht recalls them too. "Whenever the teacher would walk out of the class," says Wilkins, "he'd suddenly stand up and shake his knees back and forth against each other and make these wild aboriginal sounds. It was Jekyll and Hyde, man. The moment the teacher walked back into the room, he'd be sitting there like a little angel. His parents, people in authority, I'm sure they never saw it. He was a sweet kid, not a bad bone in his body. But there was this madman trying to get out, a part of him that wanted to be free."

Free of this body, free of this place. His father solddental products, his mother baked legendary oatmeal cookies at Christmas; they were good, careful people of German descent, the kind a boy didn't tell when he felt bad, the kind he didn't want to disappoint. They stood in the Lutheran choir each Sunday, lifting their voices to a God who would reward hard work and strict morals with a way out of a neighborhood turning black and Hispanic and chaotic even as they harmonized. In the children's choir he stood, too, slightly slouched so that noone would stare.

"Hot dogs!" Was that a movie he saw once...or was it another teen-age boy? Yelling "hot dogs!" his first day as a vendor at Yankee Stadium and stiffening when four or five people turned and looked at him. When people looked at him, he imagined what they saw and thought, and it was always worse than what they really did. "When I was in junior high," recalls a woman who was a childhood friend, "my friends and I had a crush on him."

He didn't play on athletic teams, he didn't join clubs. Mostly he spent his high school years alone, dreaming of a life reversed, a life where he effected others. "The thing about Doug," says John McCurdy, a friend since college, "is that he hurt more than other people." He would dedicate his life to changing the mental picture he had of himself, to wiping away the hurt.

He permitted only a few to see it, but he did have one chip to push out when he needed it. "By seventh grade, I saw I could make adults laugh," he says. "It was a power--like being able to fly or do back flips."

As a 13-year-old, he said a thing ridiculous almost any place in the world except America. He said he was going to be a millionaire.

UNDERSTAND, HIS PAST IS NO LONGER his; his wake, like a zipper, keeps sealing behind him as he goes. After all, who from his old neighborhood, who that he grew up with is still there? A year or two after he leaves each job, how many of the people he laughed and worried with are still there? Even if he wanted to, what markers were there to show him the way back?

His memories have become dim to him, faint, as if someone has just knocked the Coke-bottle eyeglasses off his head and now he is feeling the sidewalk for the pieces. Why bother? In Doug Tracht's country, a man does not have to remember. In Doug Tracht's country, a man can remake.

"This tall, skinny guy shows up in our dorm at Ithaca," recalls Stevenson. "He doesn't drink, he doesn't swear, he listens to classical music and he knows almost nothing about rock. He'd come back from the shower and go into the corner and turn his back to get dressed.

We're looking at him wondering how in the hell could come out of the Bronx like that. It was 1968 - this guy was living in another century. But a really nice guy, never angry at anybody. We'd work on him, trying to get him to swear. We'd get him drunk and he'd say, 'I gotta go peepee.' We'd say, 'No, Doug,' and tell him how to say it. He'd say 'I can't say that.' Finally he would, and we'd all laugh and cheer.

CALLER: "Greaseman, my husband talks like you all the time."

GREASEMAN: "What does he say?"

CALLER: "Oh, he walks in the door and says, 'Hellooooo, Sleazebag!'"

GREASEMAN: "Wellll."

CALLER: "And i say, 'Quit acting like the Greaseman.' He says, 'I'm not acting like the Greaseman, that's how i talked in Junior High.' And i say, 'You're 30 years old, you don't need to talk like junior high.'"

GREASEMAN: "Are you saying I talk like I'm in junior high, young lady? C'mon now, ain't nobody cut a slice in junior hiiiiigh!"

In America, discomfort is fuel. Doug Tracht has a rich voice, a hundred accents swimming in his head from the ethnic stew of his youth, and a dammed-up river of fuel. It had come to him, listening to a man talk on the radio one day two years before he had taken the five-hour car ride into the wooded hills of New York and arrived at Ithaca. A man could sit in a room where nobody could see him and touch people. A boy who felt feeble could suddenly have 10,000, 20,000, 50,000 watts of power. A lonely kid could be a famous deejay.

His first day on the air at the sampus station, playing Tony Bennett on a Sunday Morning, he vomited. But this was different from the date with the girl. None of the listeners saw his fear, none of them ever knew. Wasn't that freedom? He began to spend hours practicing his delivery with a tape recorder, afternoons in a friend's room sticking 45 after 45 on the record player, some nights even popping quarters in the pizza-joint jukebox in order to practice his timing so he could clip off his last word at precisely the second before the song's lyrics began. "It's called 'talking up a record,'" says Stevenson. "Nine out of 10 songs in our record collection he hadn't even been exposed to, but he'd hit them just right. He had this sixth sense about it, the kind you have when you put your heart and soul and body into something."

"The best timing," says Doug Finck, another early colleague, "of any deejay who ever lived."

He got a job playing rock music at the station in town, WTKO, seven afternoons a week, hustles to the campus station to do the night show Monday through Friday and raced up the highway to Elmira, NY, on Saturdays and Sundays for the 6-to-midnight program, then collapsed in bed and woke for classes. Quickly he saw he'd never be a millionaire, he'd never touch people, announcing time, call-letters and weather.

"..and in the meat department at the A&P, we have chicken...THIGHS...and BREASTS...ooooh, love those BREASTS..."

The kid who wouldn't swear would trudge back to his room at 1AM, exhausted, and see the guys' faces in the dorm light up. "Dougie, that A&P ad you did, I caught it in my car this afternoon - I couldn't believe it!"

"He began to realize," says Stevenson, "that the more and more he did things like that, the more notoriety he got. Nobody told you where the fence was in broadcasting. He could keep reaching his hand out further and further until he got it slapped. Out in public, he was so self-conscious, but put him in front of a microphone, and he just cut loose."

He began to experiment, to grope for the fence. He memorized the first lines of records and invented stories to tell during the musical introductions, setting up the first line as the punch line of his story. He gathered a collection of sound effects - toilet flushes, screams, glass breaking - to inrich his stories. He deepened his voice on the air, making himself sound older, bolder, strong and macho. "I'm cookin' with heavy grease," he'd growl after playing three songs without interruption. One day a man who worked with him at the station grinned and yelled out, "hey, Greaseman." Yes! On radio a man could lose his body, his past, his voice, his vulnerability - even his name. A man could be weightless on radio, a man could be free.

The Greaseman became all that mattered to him. No time for laundry, no time for washing dishes. He'd buy triple-packs of BVD underwear and T-shirst each Friday when he got his paycheck, wear each once, toss them in a pile in the corner and buy six more fresh pair the next Friday. Beside his kitchen table lay a cardboard box full of new dishes. Slap a piece of chicken on one, wolf that down, then heave the dish in the garbage can. Fifteen more minutes, gotta be on the air.

His junior year he got a job at WENE, a station that serviced Binghamton, NY. More power, more listeners, more BVDs. A receptionist at the station, a pretty Italian girl named Marie who giggled every time she heard him on the air, did something that surprised him. She fell in love with him, moved in with him and did all 18 loads of his underwear in the corner.

Yet something kept driving him on, to see how far he could roam without reaching the fence. "Now, more music," he'd boom when the news ended, "from the 5,000-watt moth-ah."

"Doug, I've got to talk with you," said station manager Andy Hubbell. "Doug, when i was in the war, 'mother' was short for -"

"Oh, no, Mr. Hubbell, what i mean is that the station is our mother. It nurtures us."

From the station's sister FM studio, he found a way to pipe sound effects over the AM airwaves without anyone knowing their source. "Do you suffer the pain and itching of hemorrhoids?" an ad would begin. From nowhere would come a blood-curdling scream. AT&T and the FBI investigated, but Doug Tracht remained anonymous, weightless...free.

Free, except for the days when the station asked him to go to a county fair or a store to broadcast his show in public. "You? You're the Greaseman?" said people who had expected a hefty, grizzled man. They gaped at this weedy young man, and he felt their disappointment.

His eyes would drop, his lips freeze, his cheeks burn. That which liberated him imprisoned him too.

At night, when he came out of the station and found a car-load of teen-agers waiting to meet the Greaseman, he began to point back to the building and throw his voice an octave higher. "The Greaseman? Sorry, he's still in there working."

HE GRADUATED FROM ITHACA AND moved on to a bigger market, WAXC in Rochester, NY. The character of the Greaseman began to take form: a woodsman who had wandered into the city, ate from dumpsters and somehow managed to land a job playing records, which he did while squatting on the toilet. So convincingly did he convey his lonliness in this urban world that a little boy called and invited him home for dinner.

It's just a role, he'd tell people. But any criticism of the Greaseman brought Doug Tracht's old uneasiness in a rush. He monitored the tape on which listeners could leave weekend messages at WAXC, and when he heard complaints about the Greaseman, he went to a phone booth and dialed the station himself, altering his voice to mimic a grandmother enthralled by the Greaseman.

He mailed dozens of sample tapes to bigger stations, looking to climb. "I'll be stick here all my life," he'd fret, when he hadn't even been there a year. Then WRC of Washington (now WKYS, but at the time a Top 40 pop station) called and offered him $19,000 to do the 10PM to 2AM show. The big time!

He walked through the station's doors in '73 and the people who only knew him by his tapes were stunned. "This tall sandy-blond kid walks in, 120 pounds dripping wet, maybe 24 but looking even younger, with a medium-range voice," says studio engineer Skip McClosky. "He sits behind a microphone and in a finger-snap becomes this beer-bellied codger with an incredibly deep voice. It was scary."

People loved him, people hated him. And some who hated him felt compelled to listen anyway. "What Doug has always understood," says Stevenson, "is that some people are two-faced, and that the vast-majority want to hear someone say those things."

"If you don't want people to know what station you're listening to," the Greaseman would growl on the air, "stick your radio in a brown paper bag."

He cooperated with a reporter for the now-defunct Washington Star-News on the condition that his real name not be used and his photo be taken from behind, a hood covering his head. When the 13th caller on a radio contest was to recieve free tickets to a concert, he would answer the first 12 in a squeaky voice so they wouldn't trouble him with any questions. Friends of co-workers who wandered in to watch were asked to leave. The mystique grew, and so did the number of fans outside the station who, while waiting for the Greaseman, watched him stalk by.

A year passed and a new station manager wanted call letters, weather and time: a disc jockey more like Doug Tracht. The Greaseman was fired. Without a microphone and transmitting tower, the Greaseman suddenly did not exist. "May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest; mamma, your sweet boy is coming home" were his last words on the air.

BUT WHERE WAS HOME? IN 1974, HE took a job at WPOP in Hartford, Conn., gnawed by fear that his career was sliding backward. By now the thick glasses were gone, replaced by contact lenses. One dad his sister stood with her back against the railing of his apartment balcony. "Hey Doug!" called a neighbor, mistaking her thin frame for his. He felt mortified. A doctor perscribed steroids. He gained a quick 20 pounds but lost them when the steroids ran out; returning for more he found a closed office, no forwarding address.

A year later, WPOP went all-news. Doud Tracht was homeless again, jobless. Back in Washington, WRC offered him a one-week trial as sidekick with its morning man. After four awkward shows, he was given an ultimatum: Tomorrow, they said, the show must be done in Doug Tracht's voice, with Doug Tracht's name.

He went to his engineer's apartment that night, where they ate canned spaghetti and listened to tapes of vintage Greaseman. Tears shone in Doug Tracht's eyes. "I've put too much of myself into the Greaseman," he said. "I can't give him up."

ANOTHER PHONE CALL CAME, ANOTHER radio station, another city. The thought of once again remaking their lives disheartened Marie, and it was one of the reasion their 19-month marriage ended.

His life jammed in the trunk of a rusted-out, champagne-colored '69 Malibu, he pulled into Jacksonville in 1975, a funny friction in his gut of lonely ach and expactant tingle. And when they rubbed, they sent a surge through him, a feeling of power that few who weren't of his culture could even understand. "I felt ruthless," he recalls. "But it was a good feeling, too." Pulling into the radio station parking lot, sliding out the passenger door because the driver's door was busted. Feeling the stares, rubbing the road dust off his face in the bathroom. Asking for the name of an apartment complex to rent in, scribling directions from the apartment manager to the grocery store, the post office. Sitting alone at night with a drink, staring out at the lights of an alien place. "Thinking," he says, "of all those people out there. Thinking 'You don't know me, but one day i'll effect your lives. One day you'll imitate me and make your friends laugh, you'll annoy your wives with my jokes.'"

Time, weather and music became secondary: The Greaseman was unchained. On Jacksonville's WAPE, a 50,000 watt rock station that could be heard as far away as Georgia and South Carolina, he changed shape once more, riding the CB craze and becoming a womanizing, red-neck, devil-may-care trucker, reveling in the feel of steel beneath his feet. "You'd have sworn," says a co-worker, "that he'd lives all his life in Jacksonville and hated Yankees."

Immediately, station management realized that it could exploit his passion for privacy, and the veil of secrecy over his other life became yet heavier. Thick burgundy curtains went up to cloak the station's control-room window, a TV interview was conducted showing only a massive close-up of his lips, a newspaper photo was published revealing only a bare foot with a cigar between two toes. At public appearances, he sweltered inside a gorilla suit. The people who came out to see the Greaseman, he noticed, were often people Doug Tracht wouldn't like. His true name was never revealed.

In a conservative city with strong fundamentalist leanings, the Greaseman caught fire. Greaseman T-shirts, Greaseman albums, a Greaseman TV show (done in heavy makeup) and a greaseman coloring book hit the market. Truckers blasted their horns and waved as they rolled past the station. A local man starting an automobile air-conditioner installation shop advertised regularly in live, wacky telephone conversations with the Greaseman and saw his business become a quarter-million-dollar-a-year one overnight. At one point, a staggering 16.2 percent of all radio listeners 12 and older in the area were tuning in the Greaseman - 45 percent of all males between 18 and 49 - and he wasselected the nation's top air personality in 1977 and 1980. "What he was doing," says Hoyle Dempsey, a co-deejay at WAPE, "was different than anyone else in radio. There was something about him that we all wanted to be."

The bigger his audience became, the higher the advertising rate his station could demand, and the more freedom he could flex behind that burgandy curtain. His listeners learned his code for female body parts - tuna fish and burrito complito meant one thing, globos grandes and niplitos bonitos if they were more at ease with breasts. In 1979, would a radio station in Paris or Rio de Janeiro have rewarded the Greaseman with a five-year contract worth - including advertising fees - $1 million?

The one in Jacksonville did. The Greaseman had found contentment. "I can emote totally, spill my guts, i can turn on the mike and say, 'Look at me, look at me!' and it's well-recieved. Once i get psyched up into creating a scene, it's like being an athlete. He doesn't think which way he's going to cut. he just does it - and the coach doesn't care as long as he crosses the goal line into glory and splendor. I'm almost a trained schizo - it just comes out and i don't even know how it's coming out, and in a corney of my brain, i'm saying, 'Hey, this is pretty neat'...Sometimes i feel like i'm posessed. I mean, sometimes i feel like i am that character. I don't plan it, it just flows. All i have is an idea and then as i'm talking all these other facets come screaming in, side doors open, stage whispers come in. And a little part of me is thinking, 'I hope it never stops.' What if i say 'go' one day and there's just the hum of equipment? I go on cold each day, and thank God, it comes."

The Girl Scouts Council in Jacksonville did not thank God. It filed a complaint with the Federal Communication Commission. "Filth sells. Sickness sells," seethed the Girl Scouts' public relations manager when nothing came of the complaint.

FCC rules prohibit "description of sexual or excretory activites or organs in a patently offensive manner." Was burrito complito patently offensive? Couldn't they see, he wondered, that he was saying it all with a twinkle in his eye?

A born-again former WAPE salesman printed and distributed a glossary of definitions for the Greaseman's code. Citizens Against Pornography, backed by local churches, mounted a petition drive against him, gay-rights activists wrote letter after letter to newspaper editors, death-row inmates threatened a lawsuit.

"Good morning, you maggots," the Greaseman had greeted them on the air in 1979, when Florida legislators decided to reinstate the death penalty. "Are you up yet? Better enjoy the sunrise. There aren't many left for you...Don't cry, let 'em fry." The day of the first execution, he played sound effects of bacon frying and a song entitles "Burn, Baby, Burn," and informed listeners he was turning down the station's 50,000 watts to 10,000 in order to facilitate the power surge for the local electric chair.

He made jokes about punching his ex-wife's teeth out. Yet privately, he told close friends her loss "was like a death in the family." Everyone who knew Doug Tracht came away talking of his sweetness. He telephones listeners at the hospital after work hours, and once, when management decided to fire a fellow deejay without notice, he threatened to quit unless the man was given two weeks to look for another job. "He made four times what any of us made," says deejay Dempsey, "and not a single person minded." Later, when his father was dying of lung cancer, he flew a shuttle flight virtually every day after work for weeks to be at his side.

And one by one, when advertisers felt offended by the Greaseman, they recieved a call from a quiet, courteous, sensetive young man who won them back. His ratings continued to soar. "There's a little bit of the Greaseman in all of us" is how he explained his popularity.

The distance between who he was at work and who he was at home still troubled him. One day in 1977 he saw his station's news director, a body builder named Allen Moore, gazing at himself in the control-room glass and flexing. "You're making progress," the Greaseman called over the studio intercom. "But there's something about that that isn't quite right."

"You ought to try it."

"Do you think I could make myself big?"

He could. He could make himself anything. He began to lift weights an hour and a half a day, four days a week, took 20 vitamin tablets a day and ate massive quantites of food. Each day, he ate four cans of tuna, four raw eggs, and drank a gallon of milk, polishing off several cans of weight-gaining formula while driving in his car. One day, watching TV, he ate so much he vomited. He came back from the bathroom and opened another can of tuna. He felt new strength well inside him. Now he knew he could do anything.

In three months, he gained 25 pounds. In a year, 45. He threw back his shoulders, wore tank-top T-shirts and grinned when people told him he looked like Arnold Schwarzenegger. "His entire facial structure changed," says Moore. "His jaw became square, his face full. It went from an accountant's face to a football player's."

By now, he had completed a night course at a Florida police academy and was a part-time volunteer cop. "A model policeman," noted a superior, Chief D.R. Horn, "and one of the most courteous fellows I've ever met."

Sometimes he worked all night patrolling with a full-time officer, then drove straight to the radio station to begin his 5:30 AM show. The employees who arrived at 9 and peeked inside the curtains saw a muscle-bound 195-pound man in full police uniform speaking into the microphone, a .357 magnum on his hip.

One day, his body-building pal Allen Moore caught him flexing in the control-room glass. "You know," said Doug, "I like it, but there's still something about this that isn't quite right..."

THERE ARE NO EXCUSES IN THIS COUNTRY, nothing to hold you back. If there is something causing you pain, change it. If you don't like your surroundings, change them. Sure, they say some people are trapped by their circumstances or education. But, hell, if I can gain 60 pounds, you can get a new education. This is America, and you have the right to change anything.

Dawn in D.C., Jan. 20, 1986: the first national observation of Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday. Through the dark, empty streets drives the Greaseman. He must be in place, waiting, when the rest begin to stir.

A shock jock, that's what people have begun to call him. All at once, he is not alone in what he does; more and more people in the land where there is nothing to hold you back, even those who wear ties to work, are tuning in to morning deejays who test the boundaries of the taboo. All at once, his frontier feels crowded. "It's not fair," he'd say. "I'm creating characters and stories, I'm weaving a tapestry or humor. The others are just saying nasty things."

He has changed form once again since returning to Washington radio in 1982. Not a trucker now, but a more sophisticated, weight-lifting narcissistic rake. His voice on air is less deep now, more his own. He looks and dresses like an NFL player in the off-season: sneakers, shorts, pullover tops, clean-cut and freshly showered. Proud of a body that he spends an hour a day keeping pumped, he has even willed himself to overcome his terror of appearing in public. "Now," says Stevenson, "there aren't many women who wouldn't look twice." The Greaseman and Doug Tracht have begun to merge.

His salary has risen dramatically, he has bought a beautiful boat and met the beautiful lady who six months later would become his wife. Out in the world, he loves blazing a trail in his profession, feeling singular. At home, he loves the sweet feel of surrender with a woman who nurtures him like a mother. Sometimes he peeks out his window in a bathrobe, waiting for her to come home, cook a gourmet meal, talk and rub his shoulders.

But now the sun is rising and he has four hours on the air to fill, to prove once more that he is different. Rapidly his mind begins to work. The King joke, that's a good one, he thinks. The one he told the year before on the slain black leader's birthday. He does not mull it long: He trusts his instincts, and besides, there is so little time for mulling. He eats his cereal, cracks his knuckles, leans into the microphone.

"Today is Martin Luther King's birthday..."

Word by word, as the joke continues, the life he has so painstakingly built begins to tremble. Soon listeners and employees at rival stations will call the Washington Post to report what he will say. Articles will appear, pressured companies will pull their advertising off the station, blacks from Harvard University will lead angry protests outside WWDC offices demanding the Greaseman be fired. A station vehicle will be smashed. A deejay with a powerful body will need bodyguards.

"...You know, I've always felt strongly that the nation should commemorate this day as a national holiday..."

Complaints will flood the FCC. The story will spread across the country. A TV editorial calling him "the insensitive boob of the year" along with newspaper columns and letters to the editor will keep stoking the issue. And using his real name. On radio, spoken in a rapid-fire code, his words had always seemed to flutter off into the air. In newsprint, uncoded, they will lie on paper growing darker and denser.

"...People should not have to work on this day, the children should all have a day off from school..."

He will apologize on radio and TV, but many would not forgive him. Inside him, one thing has not changed: He still hurts more than other people. In his home, he will pace and lose his desire to eat and wonder if, after all those years of struggling and changing to make the Greaseman feel at home inside a single body, it would be better to quit than to bear another day of this: people screaming at Doug Tracht for what the Greaseman had done.

"...In fact, I felt so strongly that I even went before Congress to lobby for making this day a national holiday..."

Station managemant will offer to suspend him without pay for a week, but the protestors will spurn that and continue to demand his firing. Finally, the demonstrations will dwindle, the Greaseman will weather the outrage and carry on.

"My show is a harmless cartoon for adults, an escape," he will explain. "I made a bad evaluation...but I made my apologies. Why do people have to keep blowing it up? The people who listen to me realize that I'm just shrieking. Hell, I don't mean nothin'. I'm an actor playing a role."

"...IN FACT, KILL FOUR MORE AND we can take the whole week off..."

"That's a goddam rotten thing to say," snarls Bennie. He snaps the radio off.

"It's just a joke," says Eddie Scott, laughing as he reaches from the back of the van and clocks the radio back on.

"That's no joke." Bennie snaps it off.

"Oh, come on." Eddie clicks it on.

Eddie is one of the Greaseman's most loyal fans, and now it is becomming a matter of a principal he cannot put into words. Bennie is a black sub-contractor who is hiring Eddie to paint a house in a Washington area, and is giving him a lift there. Eddie has lost his $16,000 can, his home, his wrestling scholarship to the University of Maryland, his good-paying job with a government-contracted company and all his plans in life as a result of a car accident a few years earlier that crushed 27 of his bones along with his lungs, his colon, spleen and liver. His girlfriend and little girl have moved out. He still owes thousands of dollars in uninsured hospital bills.

"I said keep that crap off!" yells Bennie.

Eddie snorts and clicks it back on.

The thing he had wanted to do most when they had taken the tracheal tube from his throat at Prince George's Hospital Center was to call the Greaseman. Nobody had understood that - not Eddie's family, not his friends, not even Eddie - but that was what he did week after week, dialing and listening for hours to a busy signal or unanswered ring.

Six times Bennie snaps the radio off. Six times Eddie clicks it on. Finally, Bennie pulls the van to the side of the Beltway. "Get the hell out, you prejudiced white sonofabitch," he shouts.

Eddie looks at him, then yanks up the door latch and steps out onto the shoulder of the road. The cars whip by. He slams the door, the tires spit gravel and pull away. The sun has barely risen. Rarely in his life has Eddie felt so free.